By Strength Sensei CP

Publication Date: 1996

It has become a familiar sight in every serious bodybuilding gym: massive plates loaded to the max on the 45-degree leg press – sometimes augmented with the additional weight of a dedicated training partner, riding the sled like a rodeo cowboy. This obsession with monster leg presses led one equipment manufacturer to develop a unit that can handle 6,000 pounds of plates! Even more impressive than the weights used are the elaborate rituals associated with this exercise: knee wraps tightened to an excruciating degree and a heavy-duty belt, cinched to a degree reminiscent of the old-fashion corsets of the Victorian era. This display is followed by the trainee grunting out rep after rep until reaching a crescendo, most often an ear-splitting ARGGHHHHHH until that last rep is grinded out, followed by an expression of momentary muscular exhaustion that results in the sled slamming down against the safety supports.

The appeal of such heavy-duty-ego exhibitions explains why many bodybuilders choose almost any leg exercise over the squat. After all, hoisting a metric ton on the leg press is far more impressive than a measly 300-pound deep-knee bend. But anyone who has ever painstakingly fought their way out of a heavy rock-bottom squat knows will tell you how much harder it is than pushing an angled sled a few inches, regardless of the poundage. It’s true. Nothing is more difficult, and more result producing, than the squat – nothing!

Leg presses are a valuable assistance exercise for increasing lower body strength and packing on muscle mass, but they are not a substitute for squats. (Miloš Šarčev photo)

If the squat does not comprise a major component of your leg training, you’re probably listening to the “myth-information” surrounding this exercise. To set the record straight – and hopefully get you back in the power rack – I present the following eight common myths about squatting:

Myth #1. Squats Widen the Hips. Tell that one to Olympic sprinting medalist Marlene Ottey from Jamaica. She’s a powerful squatter who toys with loads that would shame most male trainees, yet her lower body retains amazingly elegant proportions, reminiscent of Ms. Olympic Cory Everson at her best.

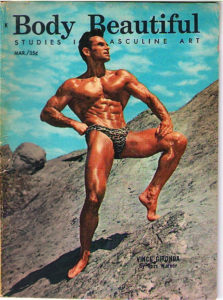

The hip-widening myth can be traced to bodybuilding guru Vince Gironda. Even though Gironda contributed many interesting ideas to the field of physique transformation, there’s no scientific or empirical evidence to corroborate his belief that squats widen the hips. When the gluteus maximus (the major butt muscle) develops, it grows back, not out, because neither its insertion nor origin points are at the hips. If squats did widen the hips, then Olympic-style lifters, athletes who devote as much as 25 percent of their training volume to squats, would be built like mailboxes.

Vince Gironda made numerous valuable contributions to the bodybuilding world, but his belief that squats widened the hips missed the mark.

Myth #2: Squats are Bad for the Knees. Not only are squats not bad for the knees, every legitimate study on this subject has shown that squats improve knee stability and therefore reduce the risk of injuries. (The National Strength and Conditioning Association has an excellent position paper on this subject with an extensive literature review – a must for any strength coach’s library. This review is called The Squat Exercise in Athletic Training.) Further, data from the Canadian National Team of Alpine Skiers suggests that regular squatting reduces not only the rate of injuries, but also the time it takes to recuperate.

When I trained the Canadian National Women’s Volleyball Team, I found that all of them suffered from varying degrees of jumpers’ knee – a form of overuse injury. To correct the problem, which I believe was partially caused by a strength imbalance in the major thigh muscles, I had these athletes perform step-ups and then gradually transition into full squats. Only one athlete still had jumpers’ knee after three months of proper training.

Providing you don’t relax or bounce in the bottom position of the squat, you’ve got nothing to worry about. When you relax, the knee joint opens up slightly, exposing the connective tissue to stress levels higher than their tensile strength. Does that mean you should never pause in the bottom position? No. It means that if you pause in the bottom position, you must keep the muscles under tension, holding the static (isometric) contraction.

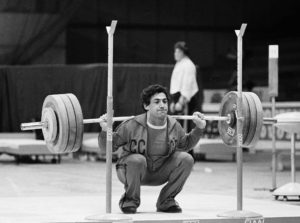

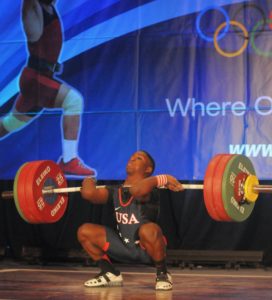

Weightlifters such as Russia’s weightlifting gold medalist Yurik Vardanyan often performed “No, No, No Squats,” which means “No belt, No knee wraps, No spotters.” If the weight is too heavy, these athletes dumped the weight behind them to the platform — of course, with bumper plates. (This photo, and lead photo of US weightlifter and Olympia Melanie Roach, by Bruce Klemens)

Myth #3. There’s Only One Way to Squat.Whether you perform squats with the barbell resting on the clavicles or on your traps, or if you use a Zane Leg Blaster instead of a safety squat bar, you’ll force adaptation and growth.

Most bodybuilders like to squat with their backs as vertical as possible, a technique that increases the forward movement of the knees. Powerlifters tend to squat by bending more from the waist to reduce forward movement of the knees. Also, to use as much weight as possible (and because the rules permit it), powerlifters often don’t squat as deeply as bodybuilders or weightlifters. From the fields of biomechanics and neurophysiology, we know that the depth of squatting, degree of leaning forward, and knee-motion patterns affect muscular recruitment patterns. We also know that the more you vary your exercises, the more motor units you can recruit.

What this means is that bodybuilders would benefit from squatting like powerlifters because they would tap into a new motor-unit pool, and the greater the motor-unit involvement, the greater the growth. Conversely, squatting deeper would enable powerlifters to increase the development of the vastus medialis (the teardrop-shaped muscle that inserts at the knee) and hamstrings muscles, thereby increasing knee stability. As Tom Platz, a bodybuilder whose leg development was set a new standard in physique competition, says, “Half squat, half leg!”

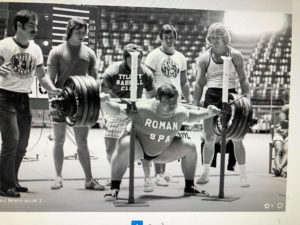

Powerlifters don’t squat as low as weightlifters and tend to use a wide-stance and lean forward, methods that enable them to use more weight than weightlifters. One master of this squat variation is Paul Wrenn, who squatted 975 pounds in 1981 and held the world record between 1979-96. (Bruce Klemens photo).

Myth #4. You Should Squat Until You Puke.There are bodybuilders who believe that exercise intensity can often be measured by how much you regurgitate. This bizarre belief was discussed in Samuel Wilson Fussell’s controversial book, Muscle: Confessions of an Unlikely Bodybuilder. There is no truth to this myth, and most vomiting can be prevented with proper conditioning and by avoiding meals of slow-to-digest protein foods immediately before a heavy workout.

Myth #5. Smith Machine Squats are Safer Than Regular Squats. This is a downright lie! My experience with the Smith machine squat is that it’s hard on the patellar and anterior cruciate ligaments, connective tissues that help stabilize the knee.

Most bodybuilders who use a Smith machine perform squats while holding their trunks vertical to minimize the involvement of the hamstrings and increase the involvement of the quadriceps. Leaning back against the bar also increases the stability of the trunk, further reducing the involvement of the hamstrings. This is not desirable, as hamstring activation is a direct antagonist to quadriceps activation at the knee, and this “co-contraction” neutralizes the harmful shearing forces on the knee. There’s more.

The bar moves on a track with a Smith machine, increasing the stability of any exercise. This increased stability decreases the requirement of the body’s neutralizer and stabilizer muscle functions. As such, the strength developed on such machines has minimal carryover to a three-dimensionally unstable environment like the free-standing squat. This is especially important for those who use weight training to improve sports performance. The bottom line is that free-weight exercises precede machine exercises, and athletes should limit their machine training to do no more than 25 percent of the total work performed.

Smith machine squats are popular with bodybuilders as they place more emphasis on the quads, but they should be used sparingly as they can be hard on the knees. (Miloš Šarčev photo)

Myth #6: Squats are bad for the back. As long as you squat with proper form, the center of mass of the barbell will not be far away from your center of gravity; this posture in itself will help prevent injury. In a misguided attempt to increase glute involvement, some personal trainers recommend squatting with a tail-under posture, keeping the back flat or slightly rounded. Lifting with this posture places excessive strain on the ligaments and other connective tissues of the back.

To protect the ligament structures of the back, squat with a slight arch in your lower back. This lifting form increases the stress on the musculature to make up for not using the ligaments to support the back. Yes, this technique may be associated with a higher incidence of the lower back muscle strain, but the alternative is a ligament injury. Considering that a muscle takes 3-8 days to recover from a mild or grade-1 tear, but a ligament sprain takes at least 21 days to heal, the decision to arch slightly becomes relatively easy.

Another important safety technique is to squat with the hands pulled-in and the elbows tucked under the bar to keep the torso upright. Also, try doing a few of your lighter sets of squats without a belt as this will strengthen the trunk muscles that help protect the back – but it’s a sound practice to wear a belt on your heavy sets!

Some beginners find squats uncomfortable on the upper back area and may try to minimize their discomfort by rolling a towel around the bar; I strongly advise against this practice. The larger diameter of the bar caused by the towel can be harmful to the neck and increases the risk of the bar rolling down the back – I’ve seen this happen on several occasions. A better idea is to use a device called the Manta Ray.

By redistributing the weight over more muscle mass, the Manta Ray minimizes the stress on the traps, and it does so without displacing the center of the mass of the bar. Powerlifting coach extraordinaire Louie Simmons from Columbus, Ohio, uses the Manta Ray for variety in training his very successful powerlifters. The only problem is that although the advertisements claim one size fits all, individual with especially large traps may find the device uncomfortable (and other individuals will put the device under their T-shirts, to make it look like they’re got bigger traps!). Another option is one of the various safety-squat bars with padded yolks that distribute the weight slightly differently than the traditional high-bar squat.

In time, most individuals will get used to the feel of the bar on the upper back. The best way to alleviate discomfort is to simply build up the traps!

Myth #7: Squats Make Athletes Slower. At his prime (and prior to his drug issues), Ben Johnson was respected by competitors not only for his lighting speed but also his prowess in the weight room and his tremendous thigh development. Ben Johnson’s leg training revolved around the squat. He reportedly could knock out reps with 600 pounds!

Squat performance can be directly related to success in track and field sprinting events, as well as in many other sports. A few great examples of the relationship between squatting and athletic performance are the successes of bobsledder Ian Danney, who front squats 418 pounds for 2 reps at a bodyweight of 185 pounds; skier Kate Pace, who back squats 264 pounds for 3 reps at a bodyweight of 150 pounds; and speed skater Michelle McKendry-Ruthven, who parallel squatted 66 reps in 60 seconds with 70 percent of her bodyweight!

Which is better for athletes, front or back squats? Although sprinting performance has been more closely correlated to front squats than back squats, these results have occurred because my sports science colleagues have varying interpretations of how the back squat should be performed (especially in regards to how low to squat). With a front squat, the weight is on the clavicles (as with a clean in weightlifting) or with the arms crossed in front. In contrast, there are many types of back-squat techniques, some more effective than others in their carryover to sprinting performance.

Weightlifters front squat because this is how the bar is positioned when they clean. Shown is Olympic hopeful CJ Cummings, who clean and jerked this American record of 337 pounds at age 14 weighing only 136 pounds. Cummings holds all the junior world records in the 160-pound bodyweight class with a 339 snatch and a 425 clean and jerk. (Bruce Klemens photos.)

Those with flexibility issues can cross their arms in front as shown here. (Miloš Šarčev photo)

Myth #8: Squats Can Damage the Heart. Squats will temporarily raise blood pressure, but the heart adapts to the stress in a positive fashion by making the left ventricle grow larger. Interestingly, studies have shown leg presses performed on a 45-degree angle will increase the blood pressure three times more than the squat. Obviously, if you suffer from cardiovascular disease or if it runs in your family, consult the appropriate health care practitioner before engaging in a serious squat program.

While I believe the squat is the “King of Lifts,” consider that squats are not the entire royal family. There are plenty of bodybuilders who have achieved extremely high levels of muscle mass by centering their leg training around hack squats, lunges, and leg presses. Likewise, many athletes have achieved the elite levels of performance without squatting – however, I believe that most of these athletes would have reached new physical heights if they performed squats.

No discussion about great squatting would be complete without a mention of Japan’s Hideaki Inaba. Although he started powerlifting at the age of 33, Inaba won 17 world championships and became the first to squat 4x bodyweight. At a bodyweight of 114 pounds, Inaba squatted 534.6 pounds. (Bruce Klemens photo).

The squat has received more than its share of praise, comment, and criticism. As far as the latter is concerned, much of it has more to do with lore than science. Surely, many athletes who have performed squats as part of their training have blown out their knees, but that doesn’t necessarily mean that squats caused the knee injury—it could have been caused from any one of a number of factors. The same follows that even though some athletes achieve excellent results without performing squats, it doesn’t mean squats shouldn’t be an integral part of any leg-training routine.

The squat has been an unfairly maligned exercise. Whether or not you choose to include it in your program is your personal decision, but base that decision on facts, not myths. Even though squatting isn’t the only way to make your legs big and strong, it’s definitely the BEST and FASTEST way!