The importance of performing a variety of training speeds for superior performance

By Strength Sensei CP, 1994

Strength training at slow speeds, especially by prolonging eccentric contractions, is valuable for stimulating muscle growth. Strength training at high speeds, especially with rapid concentric contraction, is more specific to the movements that occur in most sports. But it would be a mistake for athletes to neglect slow speed training.

I say this because training at high speeds should be performed after developing a base of maximum strength, and developing maximal strength is best achieved by performing slow movements with heavy weights. In other words, to train for speed, athletes need to train slow!

Several years ago, German sports scientist Dietmar Schmidtbleicher joined me at a pre-conference seminar for the National Strength and Conditioning Association. Those who did not attend missed out, as Schmidtbleicher is one of the foremost experts on explosive training, such as plyometrics for athletes. (For this reason, I strongly suggest you pick up the IOC Medical Commissions Publication’s Strength and Power in Sport. Schmidtbleicher wrote the chapter, “Training for Power Events.” It’s heavy reading, but if you’re a strength coach and take your profession seriously, you need to look at the science.)

Schmidtbleicher, among other experts in his field, found that muscles increase in strength faster if trained at various speeds. I also believe that before focusing on intense plyometric activities such as depth jumps, the athlete should have a foundation in maximal strength training performed at slower tempos. If not, the risk of injuries, especially overuse injuries, is much higher.

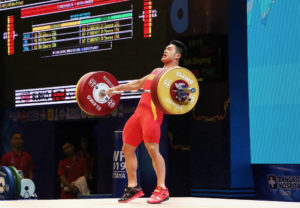

Slow-velocity training with exercises such as squats develops a strength base for high-velocity training such as snatches. Lead photo by Ryan Paiva, LiftingLife.com. This photo by Tim Scott, LiftingLife.com.

Slow-velocity training with exercises such as squats develops a strength base for high-velocity training such as snatches. Lead photo by Ryan Paiva, LiftingLife.com. This photo by Tim Scott, LiftingLife.com.

Two studies that looked at the periodization of velocity-specific training were published in the Journal of Applied Sport Science Research in 1989. In one study, researchers found moving from workouts that emphasized low-velocity training to high-velocity training produced superior results in applying force at both speeds. In the other study, researchers found that high-velocity training by itself did not produce improvements in high-velocity force production as well as training at both high and low speeds. Consider my work with Jud Logan.

Logan competed in the 1984 and 1988 Olympics before I started working with him. For Logan, I believed slow tempo deadlifts help control knee and trunk flexion during turns, whereas high-velocity training with snatches helped improved power for the release of the implement. The results?

On October 9, 1991, Logan’s best results included 77m in the 7.26 kg hammer, 86m in the 6 kg hammer, and 77.75 in the 35 lb. hammer. Over the next nine months, Logan improved his back squat from 135 kg to 180 kg. In 1992, he improved his results in all three events and earned a spot on his third Olympic team!

Although there is research suggesting that a combination of velocity speeds is not superior for producing leg power, I believe such variation is necessary for elite athletes to achieve top form.