Keys to achieving the highest levels of strength and power

Strength Sensei CP

I’ve always believed that a variety of training tempos was needed to develop explosive athletes. One strength expert who I consider a mentor of mine who was also a proponent of varying training tempo was Pierre Roy, a national weightlifting coach in Canada

Roy’s training knowledge made you think he had a Ph.D. in exercise science he wasn’t telling us about. He told me that for his weightlifters who needed to add muscle to move up a bodyweight division and get strong in a hurry, he would have them perform slow eccentric contractions during preparatory training periods. For example, 6 reps in the back squat with a 5-second eccentric contraction for multiple sets. I still believe that slow, eccentric squats are among the best and fastest ways to get athletes bigger and stronger.

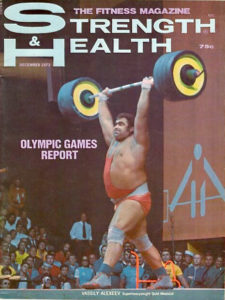

Along with Roy, many Soviet weightlifting coaches endorsed varying the tempo of weightlifting exercises for strength enhancement. One coach was Rudolf Plukfelder, whose success stories include Olympic Games weightlifting champions Vasily Alexeev, a 2x Olympic Games champion who broke 80 world records and was the first man to clean and jerk 500 pounds. He also coached David Rigert, who won Olympic gold and broke 65 world records in three bodyweight divisions. Plukfelder’s ideas were supported by Professor Alexei Medvedev, who served as head coach of the Russian weightlifting team.

Vasily Alexeev was the first man to clean and jerk 500 pounds and used a variety of lifting speeds in his workouts. (Lead photo by Tim Scott, LiftingLife.com)

As I evolved as a strength coach, I came across many weightlifting coaches from the Eastern Bloc who all believed in varying contraction speed, whether they were Hungarian, Polish, East German, or Romanian. One problem, however, was that researchers often were aiming to find the most effective, single tempo prescription.

For example, Soviet researchers S.I. Lelikov and N.N. Saxanov published a paper in 1976 entitled “The Rate of Increase in Leg Strength Depending on the Tempo of Performing Squats.” This four-month study involved 32 subjects and was designed to determine the best tempo prescription for increasing strength in the back squat.

In explaining the need for this study, the researchers said, “There is no experimental research in either the weightlifting literature (or for other types of sports, for that matter) dealing with a comparative analysis of whether a fast, moderate, or slow tempo of performing exercises, under the natural conditions of training, is the most effective means for increasing strength.” One result of the study was that the group that trained using a moderate tempo achieved the best improvement in strength gains.

While the authors are to be commended for recognizing the importance of manipulating the speed of contraction of repetitions, we have to be careful about inferring practical information from this study. There is no one perfect, “best” speed-of-contraction protocol. In the Soviet study, it would have been interesting to have one of the experimental groups perform a slow speed of contraction for the first half of the experiment and then a fast speed of contraction for the second half.

When designing tempo prescriptions, there are some general guidelines you can follow that are backed by sports science. Slow-speed lifting brings about more metabolic adaptations than high-speed lifting. High-intensity, slow-speed training using isokinetic loading is also associated with increased muscle glycogen, CP, ATP, ADP, creatine, phosphorylase, PFK, and Krebs cycle enzyme activity. Training at faster speeds does not induce these changes. Also, performing slow reps builds the connection between the mind and the muscle, making them a great finishing-off set.

One feature of my training programs that distinguishes them from the conventional workouts is that I focus on precisely controlling all aspects of the training tempo. I do this by defining the exact amount of muscular stimulus during the concentric, isometric, and eccentric contractions of every repetition. I consider it vital to address tempo as a loading parameter in all my workouts.

Of all loading parameters needed to design effective resistance-training programs, contraction speed is often misunderstood and neglected. But if you master the application of tempo prescription, you will enjoy greater control of your program, which will, in turn, result in faster and greater gains in strength and muscle development.